Although the demographics of atheism and irreligion in Mexico are hard to measure because many atheists are officially counted as catholic, at least 3 000 000 people in the 2000 National Census reported having no religion.

Now, 20 years later, there must be much more educated non-religious people in Mexico.

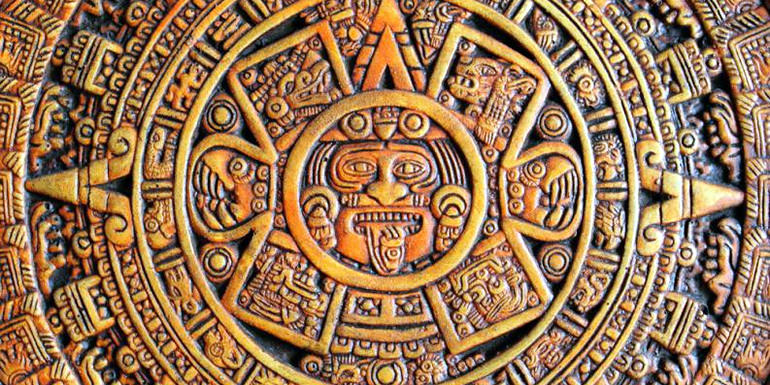

Aztec Mythology

Aztec mythology is a collection of myths of the Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures.

According to legend, the various groups who were to become the Aztecs arrived from the north into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. But little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztecs.

There are different accounts of the origin of the Aztecs.

In the myth, the ancestors of the Mexica (Aztecs) came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas (Nahuatl-speaking tribes, from tlaca, “man”) to make the journey southward, hence their name “Azteca.”

Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, “the place of the seven caves,” or at Tamoanchan (the legendary origin of all civilizations).

The Mexica/Aztecs were said to be guided by their god Huitzilopochtli, meaning “Left-handed Hummingbird” or “Hummingbird from the South.” At an island in Lake Texcoco, they saw an eagle holding a rattlesnake in its talons, perched on a nopal cactus.

This vision fulfilled a prophecy telling them that they should find their new home on that spot. The Aztecs built their city of Tenochtitlan on that site, building a great artificial island, which today is in the center of Mexico City.

This legendary vision is pictured on the Coat of Arms of Mexico.

Creation myth

According to legend, when the Mexicas arrived in the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco, they were considered by the other groups as the least civilized of all, but the Mexica/Aztecs decided to learn, and they took all they could from other people, especially from the ancient Toltec (whom they seem to have partially confused with the more ancient civilization of Teotihuacan). To the Aztecs, the Toltecs were the originators of all culture; “Toltecayotl” was a synonym for culture. Aztec legends identify the Toltecs and the cult of Quetzalcoatl with the legendary city of Tollan, which they also identified with the more ancient Teotihuacan.

Because the Aztecs adopted and combined several traditions with their own earlier traditions, they had several creation myths. One of these, the Five Suns describes four great ages preceding the present world, each of which ended in a catastrophe, and “were named in the function of the force or divine element that violently put an end to each one of them”. Coatlicue was the mother of Centzon Huitznahua (“Four Hundred Southerners”), her sons, and Coyolxauhqui, her daughter. She found a ball filled with feathers and placed it in her waistband, becoming pregnant with Huitzilopochtli. Her other children became suspicious as to the identity of the father and vowed to kill their mother. She gave birth on Mount Coatepec, pursued by her children, but the newborn Huitzilopochtli defeated most of his brothers, who became the stars. He also killed his half-sister Coyolxauhqui by tearing out her heart using a Xiuhcoatl (a blue snake) and throwing her body down the mountain. This was said to inspire the Aztecs to rip the hearts out of their victims and throw their bodies down the sides of the temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, who represents the sun chasing away the stars at dawn.

Our age (Nahui-Ollin), the fifth age, or fifth creation, began in the ancient city of Teotihuacan[citation needed]. According to the myth, all the gods had gathered to sacrifice themselves and create a new age. Although the world and the sun had already been created, it would only be through their sacrifice that the sun would be set into motion and time as well as history could begin. The most handsome and strongest of the gods, Tecuciztecatl, was supposed to sacrifice himself but when it came time to self-immolate, he could not jump into the fire. Instead, Nanahuatl the smallest and humblest of the gods, who was also covered in boils, sacrificed himself first and jumped into the flames. The sun was set into motion with his sacrifice and time began. Humiliated by Nahuatl’s sacrifice, Tecuciztecatl too leaped into the fire and became the moon.

Pantheon

Water deities

- Tlaloc, god of rain and lightning and thunder. He is a fertility god

- Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of water, lakes, rivers, seas, streams, horizontal waters, storms, and baptism

- Huixtocihuatl, goddess of salt

- Opochtli, god of fishing and hunting

Fire deities

- Xiuhtecuhtli, god of fire and time

- Chantico, goddess of firebox and volcanoes

- Xolotl, the god of death, is associated with Venus as the Evening Star (Double of Quetzalcoatl)

Death deities

- Mictlantecuhtli, god of the dead, ruler of the Underworld

- Mictecacihuatl, goddess of the dead, ruler of the Underworld

- Xolotl, the god of death, is associated with Venus as the Evening Star (Double of Quetzalcoatl)

Sky deities

- Tezcatlipoca, god of providence, the darkness and the invisible, lord of the night, ruler of the North

- Xipe-Totec, god of force, lord of the seasons and rebirth, ruler of the East

- Quetzalcoatl, god of the life, the light and wisdom, lord of the winds and the day, ruler of the West

- Huitzilopochtli, god of the war, lord of the sun and fire, ruler of the South

- Xolotl, god of death, associated with Venus as the Evening Star (Double of Quetzalcoatl)

- Ehecatl, god of wind

- Tlaloc, god of rain and lightning and thunder. He is a fertility god

- Coyolxauhqui, goddess and leader of the Centzonhuitznahua, associated with the moon

- Meztli, goddess of moon

- Tonatiuh, god of sun

- Centzonmimixcoa, 400 gods of the northern stars

- Centzonhuitznahua, 400 gods of the southern stars

- Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, god of the morning star (Venus)

Lords of the Night

- Xiuhtecuhtli, god of fire and time

- Tezcatlipoca, god of providence, the darkness and the invisible, lord of the night, ruler of the North

- Piltzintecuhtli, god of the visions,associated with Mercury (the planet that is visible just before sunrise or just after sunset) and healing

- Centeotl, god of maize

- Mictlantecuhtli, god of the Underworld

- Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of water, lakes, rivers, seas, streams, horizontal waters, storms and baptism

- Tlazolteotl, goddess of lust, carnality, sexual misdeeds

- Tepeyollotl, god of the animals, darkened caves, echoes and earthquakes. Tepeyollotl is a variant of Tezcatlipoca, associated with mountians

- Tlaloc, god of rain and lightning and thunder. He is a fertility god

Lords of the Day

- Xiuhtecuhtli, god of fire and time

- Tlaltecuhtli, old god of earth (changed in the landscape and atmosphere)

- Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of water, lakes, rivers, seas, streams, horizontal waters, storms and baptism

- Tonatiuh, god of the Sun

- Tlazolteotl, goddess of lust, carnality, and sexual misdeeds

- Mictlantecuhtli, god of the Underworld

- Mictecacihuatl, goddess of the Underworld

- Centeotl, god of maize

- Tlaloc, god of rain and lightning and thunder. He is a fertility god

- Quetzalcoatl, god of the life, light and wisdom, lord of the winds and the day, ruler of the West

- Tezcatlipoca, god of providence, the darkness and the invisible, lord of the night, ruler of the North

- Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, god of dawn

- Citlalicue, goddess of female stars (Milky Way)

- Citlalatonac, god of female stars (Husband of Citlalicue)

Earth deities

- Xipe-Totec, god of force, lord of the seasons and rebirth, ruler of the East

- Tonacatecuhtli, god of sustenance associated with Ometecuhtli

- Tonacacihuatl, goddess of sustenance associated with Omecihuat

- Tlaltecuhtli, old god of earth (changed in the landscape and atmosphere)

- Chicomecoatl, goddess of agriculture

- Centeotl, god of the maize associated with the Tianquiztli (Pleiades)

- Xilonen, goddess of tender maize

Matron goddesses

- Coatlicue, goddess of fertility, life, death and rebirth

- Chimalma, goddess of fertility, life, death and rebirth

- Xochitlicue, goddess of fertility, life, death, and rebirth

- Itzpapalotl, obsidian butterfly, leader of the Tzitzimitl

- Toci, goddess of health

Maya Mythology

Maya mythology is part of Mesoamerican mythology and comprises all of the Maya tales in which personified forces of nature, deities, and the heroes interacting with these play the main roles. Other parts of Maya oral tradition (such as animal tales and many moralizing stories) do not properly belong to the domain of mythology, but rather to legend and folk tale.

Sources

The oldest written Maya myths date from the 16th century and are found in historical sources from the Guatemalan Highlands. The most important of these documents is the Popol Vuh which contains Quichean creation stories and some of the adventures of the Hero Twins, Hunahpu, and Xbalanque.

Yucatán is an equally important region. The Books of Chilam Balam contain mythological passages of great antiquity, and mythological fragments are found scattered among the early-colonial Spanish chronicles and reports, chief among them Diego de Landa’s Relación, and in the dictionaries compiled by the early missionaries.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, anthropologists and local folklorists committed many stories to paper. Even though most Maya tales are the results of a historical process in which Spanish narrative traditions interacted with native ones, some of the tales reach back well into pre-Spanish times. Now, at the beginning of the 21st century, the transmission of traditional tales has entered its final stage. Fortunately, however, this is also a time in which the Mayas themselves have begun to salvage and publish the precious tales of their parents and grandparents.

Important mythical themes

In the Maya narrative, the origin of many natural and cultural phenomena is set out, often with the moral aim of defining the ritual relationship between mankind and its environment. In such a way, one finds explanations about the origin of the heavenly bodies (Sun and Moon, but also Venus, the Pleiades, the Milky Way); the mountain landscape; clouds, rain, thunder, and lightning; wild and tame animals; the colors of the maize; diseases and their curative herbs; agricultural instruments; the steam bath, etc. The following more encompassing themes can be discerned.

Creation and end of the world

The Popol Vuh describes the creation of the earth by the wind of the sea and sky, as well as its sequel. The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel relates the collapse of the sky and the deluge, followed by the raising of the sky and the erection of the five World Trees. The Lacandons also knew the tale of the creation of the Underworld.

The Corn Men

The Popol Vuh gives a sequence of four efforts at creation: First were animals, then wet clay, and wood, then last, the creation of the first ancestors from maize dough. To this, the Lacandons add the creation of the main kind groupings and their ‘totemic’ animals. The creation of humankind is concluded by the Mesoamerican tale of the opening of the Maize (or Sustenance) Mountain by the Lightning deities.

Actions of the heroes: Arranging the world

The best-known hero myth is about the defeat of a bird demon and of the deities of disease and death by the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque. Of equal importance is the parallel narrative of a maize hero defeating the deities of Thunder and Lightning and establishing a pact with them. Although its present spread is confined to the Gulf Coast areas, various data suggest that this myth was once a part of Mayan oral tradition as well. Important mythological fragments about the heroic reduction of the jaguars have been preserved by the Tzotziles.

Marriage with the Earth

This mythological type defines the relation between mankind and the game and crops. An ancestral hero – Xbalanque in a Kekchi tradition – changes into a hummingbird to woo the daughter of an Earth God; the hero’s wife is finally transformed into game, bees, snakes, and insects, or the maize. If the hero gets the upper hand, he becomes the Sun, his wife the Moon. A moralistic Tzotzil version has a man rewarded with a daughter of the Rain Deity, only to get divorced and lose her again.

Origin of Sun and Moon

The origin of the Sun and Moon is not always the outcome of a Marriage with the Earth. From Chiapas and the western Guatemalan Highlands comes the tale of Younger Brother and his jealous Elder Brethren: Youngest One becomes the Sun, his mother becomes the Moon, and the Elder Brethren are transformed into wild pigs and other forest animals. In a comparable way, the Elder Brethren of the Popol Vuh Twin myth are transformed into monkeys, with their younger brothers becoming Sun and Moon.

Reconstructing pre-Spanish mythology

Although a sort of ‘strip books’ may once have existed, it is doubtful that mythical narratives were ever completely rendered hieroglyphically. The three surviving Mayan books are mainly of a ritual and also (in the case of the Paris Codex) historical nature, and contain few mythical scenes. As a consequence, depictions on temple walls, stelae, and movable objects (especially the so-called ‘ceramic codex’) are used to aid the reconstruction of pre-Spanish Mayan mythology.

The main problem with depictions is defining what constitutes a mythological scene, for any given scene might in principle also represent a moment in a ritual sequence, a visual metaphor stemming from oral literature, a scene from mundane life, or a historical event. It is, in any case, clear that the Twin myth – albeit in a version that considerably diverged from the Popol Vuh – already circulated in the Classic Period. In some cases, ancient Mayan myths may only have been preserved by neighboring peoples; the narrative of the principal Maya maize god, and, to a lesser extent, that of the Bacabs are cases in point. As the process of hieroglyphic decipherment proceeds, the short explanatory captions often included within the scenes will hopefully be restored to their original eloquence, and make the ancient narrative come to life more fully.

Christian Mythology

In actuality, catholic Christianity is the dominant religion in Mexico, representing about 82.7% of the total population as of 2010. In recent decades the number of Catholics has been declining, due to the growth of other Christian-based sects – especially various protestant churches and Mormonism – which now constitute 8% of the population, and non-Christian religions (1.9%). Conversion to non-catholic denominations has been considerably slower than in Central America, and central Mexico remains one of the most catholic areas in the world.

Mexico is a secular country and has allowed freedom of religion since the mid-19th century. Traditional protestant denominations and the open practice of Judaism established themselves in the country during that era. Modern growth has been seen in evangelical Protestantism, Mormonism, and folk religions, such as mexicayotl. Buddhism and Islam have both made limited inroads through immigration and conversion.

Religion and the state

The Mexican constitution of 1917 imposed limitations on the roman catholic church in Mexico and sometimes codified state intrusion into religious matters. The government does not provide financial contributions to the religious institutions, nor does the roman catholic church participate in public education. Christmas is a national holiday and every year during Easter and Christmas all schools in Mexico, public and private, send their students on vacation.

Regrettably, in a major reversal of the Mexican state’s restrictions on religion, the constitution was amended in 1992 lifting almost all restrictions on the religions, including granting all religious groups legal status, conceding them limited property, and lifting restrictions on the number of priests in the country. Until recently, priests did not have the right to vote, and luckily even now they cannot be elected to public office.

In general, the Christian mythology of Mexico is the same as that of other countries. The only notable difference is some local saints and of course the legend of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

The Legend of Guadalupe

For more than three hundred years, the Virgin Mary of Guadalupe has been celebrated and revered in Mexico as the patroness of Mexican and Indian peoples, and as the queen of the Americas.

She stands on home altars, lends her name to men and women alike, and finds herself at rest under their skin in tattoos. Guadalupe’s image proliferates on candles, decals, tiles, murals, and old and new sacred art.

Churches and religious orders carry her name, as do place names and streets. Far from vulgarizing her image, these items personalize her and maintain her presence in daily life. She is prayed to in times of sickness and war and for protection against all evils.

The legend of Guadalupe begins in December 1531 in Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) when the Virgin Mary appeared four times to the Indian peasant Juan Diego. He was on his way to mass when a beautiful woman surrounded by a body halo appeared to him with the music of songbirds in the background.

As the birds became quiet, Mary announced: “I am the entirely and ever-virgin, Saint Mary”. Assuring Juan Diego that she was his “compassionate mother” and that she had come out of her willingness to love and protect “all folk of every kind, she requested that he build a temple in her honor at the place where she stood, Tepeyac Hill, on the eastern edge of Mexico City. (This spot has been identified as the site where once stood a temple to the Aztec goddess Tonantzin.)

Juan Diego went directly to the bishop of Mexico, Zumarraga, to relate this wondrous event. The churchman was skeptical and dismissed the humble peasant, who then returned to Tepeyac Hill to beseech the Virgin Mary to find a more prominent person who was less “pitiably poor” than he to do her bidding. Rejecting his protestations, the virgin urged him to return to the bishop and “indeed say to him once more how it is I myself, the ever-virgin saint Mary, mother of god, who am commissioning you.”

Juan Diego returned to the churchman’s palace after mass waited, and was finally able to enter his second plea on behalf of the virgin. This time, Zumarraga asked the humble native to request a sure sign directly from the “heavenly woman” as to her true identity. The bishop then had some members of his staff follow Juan Diego to check on where he went and whom he saw.

The next day, Juan Diego hastened to the bedside of his dying uncle, Juan Bernadino. The old man, gravely ill, begged his nephew to fetch a priest for the last rites of the church. The following morning, before dawn, Juan Diego set off on this mission. He tried to avoid the virgin because of his uncle’s worsening condition, but she intercepted him and asked: “Whither are you going?” He confessed that it was on behalf of his uncle that he was rushing to summon a priest. During this third meeting, she assured him that the uncle was “healed up”, as she had already made a separate appearance to him. This visitation would start a tradition of therapeutic miracles associated with “our lady of Guadalupe”. She also comforted Juan Diego with the assurance that she would give him sure proof of her real identity.

On December 12, 1531, the virgin appeared to Juan Diego for the fourth time and bade him go to the top of Tepeyac Hill and pick “Castilian garden flowers” from the normally barren summit.

She helped him by “taking them up in her own hands” and folding them into his cloak woven of maguey plant fibers. Juan Diego then set off to Zumarraga’s palace with this sure sign of the virgin Mary of Guadalupe’s identity.

As he unwrapped his cloak, the flowers tumbled at the churchman’s feet, and “suddenly, upon that cloak, there flashed a portrait, where sallied into view a sacred image of that ever virgin holy Mary, mother of god.”

This imprint of the Virgin Mary of Guadalupe, the “miraculous portrait” as it is often called, hangs today in the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City.

Since then Juan Diego never saw his halo woman again, but fortunately for the churchmen, the legend managed to spread and become popular, and until now almost all Mexicans still believe in this old legend.

It is difficult to say what actually happened: whether the Spaniards fooled the Indians or vice versa. And who did the Mexican ancestors pray to in the temple built on the sacred site of the goddess Tonatzin? We’ll probably never know.

However, it is clear that the timing of Juan Diego’s “vision” was ideal for the Christian church. In the end, it made no difference to which “celestial chancellery” the brand-new Christians sent their prayers since Catholicism was successfully gaining a foothold in Mexico.